FOOTBALL in New Jersey

The definitive history.

American football traces its roots back to the Rutgers campus, where on November 6, 1869 a game was played between Rutgers and Princeton, with the home team winning 6 to 4. The game played by the two school resembled a mix of rugby and soccer, both of which had been imported by students from the other side of the Atlantic. Few of the conventions familiar to today’s fans were in use at this time— the line of scrimmage, forward pass and drawn-up plays were still many years away. The following weekend, Princeton hosted and won a return match between the two schools, 8–0. American football traces its roots back to the Rutgers campus, where on November 6, 1869 a game was played between Rutgers and Princeton, with the home team winning 6 to 4. The game played by the two school resembled a mix of rugby and soccer, both of which had been imported by students from the other side of the Atlantic. Few of the conventions familiar to today’s fans were in use at this time— the line of scrimmage, forward pass and drawn-up plays were still many years away. The following weekend, Princeton hosted and won a return match between the two schools, 8–0.

The culture of sports was just beginning to emerge in the United States at this time. The Civil War had helped to transform what had once been regarded as gentlemen’s pastimes into competitive games. Football was perhaps the ultimate expression of this trend. It was a brutal, physical contest of strength and courage.

During the 1870s and 1880s, football evolved—often by trial and error—under the auspices of northeastern universities. Student athletes held annual conventions to discuss changes to the rules. These meetings were taken very seriously. Walter Camp of Yale was the game’s greatest innovator during this era. Football's best team was Princeton. Among the Tigers' star players in the 1880s and 1890s were Edgar Allen Poe (the poet’s nephew) and his brothers, a trio of bruising blockers named Arthur Wheeler, Jesse Riggs (left)and Langdon Lea, and two great runners, Philip King and Addison Kelly. During the 1870s and 1880s, football evolved—often by trial and error—under the auspices of northeastern universities. Student athletes held annual conventions to discuss changes to the rules. These meetings were taken very seriously. Walter Camp of Yale was the game’s greatest innovator during this era. Football's best team was Princeton. Among the Tigers' star players in the 1880s and 1890s were Edgar Allen Poe (the poet’s nephew) and his brothers, a trio of bruising blockers named Arthur Wheeler, Jesse Riggs (left)and Langdon Lea, and two great runners, Philip King and Addison Kelly.

During this time it is believed that a handful of Princeton football players—both active and graduated—played for pay in games in Pennsylvania. One of the first “pros” was Princeton grad Sport Donnelly, who was paid to play for (and also coach) the Allegheny Athletic Association team in 1892. Another former Princeton star, Lawson Fiscus, received $20 a game from another club in the Keystone State during the 1894 season.

By the turn of the century, a handful of New Jersey football clubs had begun openly paying their best players. The Oreos Athletic Club, based in Asbury Park, was one of the top professional teams of the era. So too was the Orange Athletic Club, which had started compensating key players as early as 1890. Both teams competed in world championship football tournaments in the early 1900s. In 1902, Orange actually faced the Syracuse Athletic Club in the final game of the first professional football “world series” on an indoor field at Madison Square Garden. Orange lost, 36–0.

COLLEGE BALL IN THE 20TH CENTURY

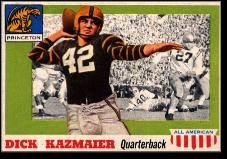

Princeton held sway over college football until World War I, however other schools around the country hired their former players to coach and eventually surpassed the Tigers. Princeton did manage to hold its own during the 1920s and 1930s. The 1935 squad—led by All-American and Heisman Trophy finalist Pepper Constable—went undefeated. The Tigers’ last All-American was Dick Kazmaier. He led Princeton to an unbeaten season and share of the national title in 1950, and won the Heisman Trophy in 1951. Princeton held sway over college football until World War I, however other schools around the country hired their former players to coach and eventually surpassed the Tigers. Princeton did manage to hold its own during the 1920s and 1930s. The 1935 squad—led by All-American and Heisman Trophy finalist Pepper Constable—went undefeated. The Tigers’ last All-American was Dick Kazmaier. He led Princeton to an unbeaten season and share of the national title in 1950, and won the Heisman Trophy in 1951.

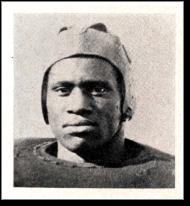

Rutgers enjoyed less success in the early years, but fielded a consistently strong team. In 1917 and 1918, the school boasted the nation’s top player, Paul Robeson. He was a devastating blocker and tackler, and one of the few African-American stars playing for a major college at the time.

In the years after World War II, Rutgers increasingly found itself being out-recruited for local talent by schools from Pennsylvania, particularly Penn State. This led to a decline in fortunes that lasted for more two generations. Things changed after the Scarlet Knights joined the Big East in 1991. In 2001, Greg Schiano was hired as head coach. In 2006, Rutgers earned a Top 20 ranking and Schiano was named NCAA Coach of the Year. In the years after World War II, Rutgers increasingly found itself being out-recruited for local talent by schools from Pennsylvania, particularly Penn State. This led to a decline in fortunes that lasted for more two generations. Things changed after the Scarlet Knights joined the Big East in 1991. In 2001, Greg Schiano was hired as head coach. In 2006, Rutgers earned a Top 20 ranking and Schiano was named NCAA Coach of the Year.

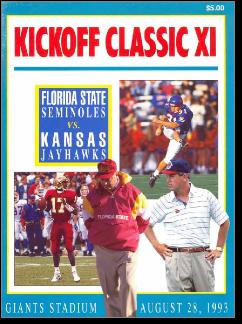

In the 1970s, after the Meadowlands Sports Complex was completed, New Jersey made a bid to take a more prominent role on the college football scene. In 1978, the first Garden State Bowl was played. Cold weather made the game unpopular with teams and fans, so the idea was abandoned in the early 1980s. Instead of December, the powers that be started looking at August. In 1983, the inaugural Kickoff Classic was played. It served as college football’s unofficial Opening Day. This event proved more popular. It lasted for 20 years.

NEW JERSEY AND THE NFL

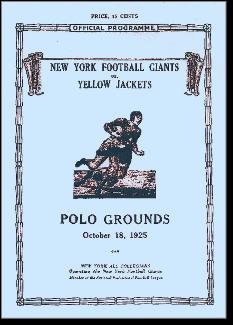

The greatest impact of the Meadowlands, of course, was on the pro football scene. Prior to the 1970s, New Jersey had an active semipro football scene, however its history in major-league professional football was virtually non-existent. When the NFL began play it concentrated its teams in the industrial midsection of the country. New Jersey football fans had to cross into neighboring state to see NFL stars. They could watch the Frankford Yellow Jackets, who played outside Philadelphia and, starting in 1925, they could also see the New York Giants play in Manhattan’s Polo Grounds. The greatest impact of the Meadowlands, of course, was on the pro football scene. Prior to the 1970s, New Jersey had an active semipro football scene, however its history in major-league professional football was virtually non-existent. When the NFL began play it concentrated its teams in the industrial midsection of the country. New Jersey football fans had to cross into neighboring state to see NFL stars. They could watch the Frankford Yellow Jackets, who played outside Philadelphia and, starting in 1925, they could also see the New York Giants play in Manhattan’s Polo Grounds.

Two pro football teams did call New Jersey home. In 1926, Newark fielded a club called the Bears in the American Football League. This was a pro league built around superstar Red Grange. Bill Edwards, a star at Princeton, was commissioner of the AFL. The league played just one season before folding. The Bears—led by Georgia Tech legend Doug Wycoff—only made it through four games. They tied their first contest 7–7 and failed to score again in three subsequent losses.

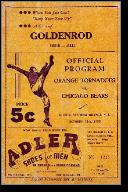

New Jersey’s second big-time pro team—and first NFL team—was the Tornadoes. The Tornadoes were based in Orange, and were one of many independent semipro teams on the East Coast that turned a profit in the 1920s. In 1929, the owners of the Tornadoes accepted the NFL’s offer to replace the defunct Duluth Eskimos. They fielded a decent team led by player-coach Jack Depier and backs Carl Waite and Frank Kirkleski. They were a very good defensive team, but did not score many point, finishing with 3 wins, 5 losses and 4 ties. In 1930, the Tornadoes moved to Newark, where they went 1–10–1 in their second and final NFL campaign. The season was noteworthy in that several games in Newark were played at night, under the lights—a rarity in pro sports at the time. New Jersey’s second big-time pro team—and first NFL team—was the Tornadoes. The Tornadoes were based in Orange, and were one of many independent semipro teams on the East Coast that turned a profit in the 1920s. In 1929, the owners of the Tornadoes accepted the NFL’s offer to replace the defunct Duluth Eskimos. They fielded a decent team led by player-coach Jack Depier and backs Carl Waite and Frank Kirkleski. They were a very good defensive team, but did not score many point, finishing with 3 wins, 5 losses and 4 ties. In 1930, the Tornadoes moved to Newark, where they went 1–10–1 in their second and final NFL campaign. The season was noteworthy in that several games in Newark were played at night, under the lights—a rarity in pro sports at the time.

During the latter part of the 1930s, pro football gained a tenuous foothold in the East as a minor-league sport. One of these organizations, the American Professional Football Association, was centered in the NY-Metro area, with all but one of its teams within a day’s driving distance. In 1938, Tim Mara, owner of the NFL Giants, purchased a franchise and located it in Jersey City. He kept the name Giants and had his son, John, run the club. Bill Owen, brother of coach Steve Owen, performed coaching duties for Jersey City. Led by superstar Ken Strong—who had been temporarily blackballed by the NFL—the minor-league Giants won the Association title in 1938 and Strong was its scoring champion. In 1939, the Newark Tornadoes were purchased by George Halas of the Chicago Bears. He changed the team‘s name to Bears and stocked with talent that didn’t make the Chicago roster. Newark’s stars included Joe Zeller and Gene Ronzani, two veterans who probably could have starred for a number of NFL teams. They led the Bears to the 1939 championship with a little help from Sid Luckman. Both the Giants and Bears used their Association clubs to incubate talent and park injured or aging players. Thus the New Jersey clubs became pro football’s first true farm teams.

The APFA had teams in other New Jersey cities, including the Union City Reds, Paterson Panthers and Clifton Wessingtons. With a few exceptions, the players on these teams worked regular jobs during the week and pulled on the pads for games on Saturday, Sunday or the occasional weeknight game. The league also welcomed a handful of African-American stars who had been shunned by the NFL. George Burgin, a halfback, played briefly for the Torandoes. Ozzie Simmons, a huge college star at Iowa, went undrafted by the NFL and took his game to Paterson. The APFA’s top black player was Joe Lillard, who performed for both the Reds and Wessingtons in the late 1930s. Lillard was the “last” African-American star in the NFL, having been the best player on the woeful Chicago Cardinals. He was a magnificent all-around athlete who played pro basketball for the Savoy Big Five in Chicago and pro baseball for the Chicago American Giants. The Cards cut him loose as Depression-era rosters contracted, citing his lack of commitment to football as the primary reason.

The American Professional Football Association suspended operations during the war, then re-started in 1946 as the rechristened American Football League. The Giants and Bears (renamed the Bombers) were among six clubs that served as farm teams for NFL squads. The league lasted until 1950.

PRO BALL RETURNS TO BRICK CITY

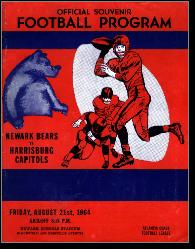

For two years in the 1960s, Newark fielded a pro football team called the Bears in the short-lived Atlantic Coast Football League. The ACFL operated for 12 seasons between 1962 and 1973, with a handful of clubs operating as minor league affiliates for NFL teams, including the Saints, Colts, Jets, Bills and Patriots. The ACFL featured teams from Maine to Florida, and guaranteed players at least $100 a game. The Newark Bears were the ACFL’s best team during their two seasons in the league. In 1963, they went 11–1 and defeated the Springfield Acorns in the championship game, 23–6. The schedule expanded to 14 games in 1964 and the Bears went 12–1–1. They reached the championship game again, but lost to the Boston Sweepers 14–10 in a game played in Newark.

The Bears played their home games at Newark Schools Stadium at Bloomfield and Roseville Avenues; the facility was nicknamed the Old Lady of Bloomfield Ave. Today, Barringer and East Side High Schools play their home football games at this location in a newly constructed stadium. The old stadium had a seating capacity of 18,000. The team was owned by Tom Granatell; his son, Chuck (below), dressed up in a bear costume and served as the team mascot. The players wore blue and white uniforms.

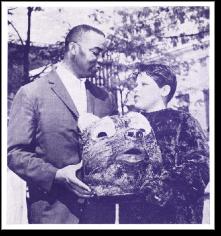

League secretary and team GM Sol Rosen ended up buying the team from Granatell when they decided to move to the Continental Football League in 1965. The team’s main supporters in Newark were local car dealerships and breweries. Monte Irvin (right), who worked for Rheingold, was a familiar face at games.

The Bears were coached by NFL Hall of Famer Steve Van Buren, with help from another Canton enshrinee, Alex Wojiechowicz. The stars of the team were receivers Reggie Lee and Dent Allen, and Bill Shockley, a defensive back and kicker. In 1960, Shockley (below right) had scored the first points in the history of the New York Jets franchise.

The Bears’ fight song was sung to the old tune “Smiles”…

There are Bears in the west that roam the Rockies.

There are Bears that swim and climb up trees.

There are Bears that warn about leaving campfires, too.

There are Bears that are seen in the zoo.

There are Bears that hibernate in winter.

There are Bears that do a trick or two.

But the Bears that I love the most, yes sir,

Are the Bears dressed in white and blue.

In 1969, the ACFL’s Charleston Rockets moved to Newark and became the Jersey Jays.

The Jays were coached by former Jet assistant Nick Cutro and starred former All-American

Milton Balkum. They operated as a farm team for the Clev eland Browns. eland Browns.

Also, according to legend, on the club for a handful of games was a 6’6” lineman who would gain fame a few years later. Clarence Clemons, who played football for Maryland State College in the 1960s, was briefly on the roster. Many of the Jays gathered at Knobby’s 52 during the week, and Clemons’s teammates recall him playing the saxophone at these get-togethers.

PRO FOOTBALL AT THE MEADOWLANDS

In 1976, the Giants moved to the Meadowlands and christened their then-state-of- the-art arena Giants Stadium. In 1984, they were joined as co-tenants by the New York Jets. The Jets had tried unsuccessfully to convince New York City to renovate Shea Stadium, their home for two decades.

In the 34 seasons NFL football was played at the Meadowlands, Giants Stadium was the site of several famous moments. The most famous might better be characterized as infamous. A bungled handoff at the end of what appeared to be a Giants victor y over the Eagles was returned for the winning TD by Philadelphia’s Herman Edwards. Philly fans call it the Miracle in the Meadowlands. Giant fans refer to it grimly as The Fumble. y over the Eagles was returned for the winning TD by Philadelphia’s Herman Edwards. Philly fans call it the Miracle in the Meadowlands. Giant fans refer to it grimly as The Fumble.

Among the brighter spots in Giants Stadium history were the Giants’ first playoff victories in their new home, at the end of the 1985 season. They beat the 49ers 17– 3 and then the Redskins 17–0 in the NFC Championship, earning a berth in Super Bowl XXI. In 2000, the Jets thrilled their fans in a Monday Night Football game against the Dolphins. The Jets fell behind Miami 30–7 before roaring back to win 40–37.

In 2001, the Giants hosted the high-powered Minnesota Vikings in the NFC Championship Game and shocked the experts by shutting them out 41–0.

In 2005, a game between the Giants and Saints was played in the Meadowlands following Hurricane Katrina. Because the game had originally been scheduled for the Louisiana SuperDome, the Saints were the home team—and their end zone was painted with their team logo and colors.

In the Jets’ final game in Giants Stadium, they defeated the Bengals 37–0 to earn a spot in the playoffs. Rookie Mark Sanchez would lead the team to within one victory of the Super Bowl.

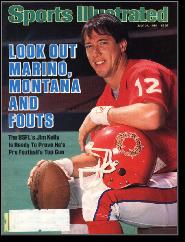

There was a third pro football team that called Giants Stadium home. The New Jersey Generals of the United States Football  League played in the Meadowlands from 1983 to 1985, after which the USFL went out of business. The Generals made an immediate splash by signing Herschel Walker, the Heisman Trophy winner. Walker was an underclassman, which meant he was off-limits to the NFL. Joining Walker on the generals were Brian Sipe, Jim LeClair, Kent Hull, Gary Barbaro, Maurice Carthon and Doug Flutie. Had the USFL stayed afloat in 1986, Hall of Famer Jim Kelly (left) would have been the team’s quarterback. League played in the Meadowlands from 1983 to 1985, after which the USFL went out of business. The Generals made an immediate splash by signing Herschel Walker, the Heisman Trophy winner. Walker was an underclassman, which meant he was off-limits to the NFL. Joining Walker on the generals were Brian Sipe, Jim LeClair, Kent Hull, Gary Barbaro, Maurice Carthon and Doug Flutie. Had the USFL stayed afloat in 1986, Hall of Famer Jim Kelly (left) would have been the team’s quarterback.

The Meadowlands also served as the site of the 1985 USFL Championship Game—the final USFL contest ever played. The Baltimore Stars beat the Oakland Invaders, 28–24. The Meadowlands also served as the site of the 1985 USFL Championship Game—the final USFL contest ever played. The Baltimore Stars beat the Oakland Invaders, 28–24.

In 2010, the Jets and Giants moved into New Meadowlands Stadium, a modern arena constructed a stone’s throw from Giants Stadium. The Jets had hoped to move back to New York when their 25-year lease expired, but could not convince the city to construct a stadium on Manhattan’s West Side. In their first season at the new stadium, the Jets made the playoffs and advanced to the AFC Championship Game. The Giants went 10–6 but missed out on a Wild Card berth because of the NFL’s tie- breaking rules. In 2011, MetLife negotiated the naming rights to the stadium.

New Jersey College Football

Consensus All-Americans

1889— Hec Cowan, TACKLE (right)

William George, CENTER

Edgar Allan Poe, BACK

Roscoe Channing, BACK

Knowlton “Snake” Ames, BACK

1890— Ralph Warren, END

Jesse Riggs, GUARD

Shep Homans, BACK

1891— Jesse Riggs, GUARD

Philip King, BACK

Shep Homans, BACK

1892— Arthur Wheeler, GUARD (right)

Philip King, BACK

1893— Thomas Trenchard, END

Langdon Lea, TACKLE (right) Langdon Lea, TACKLE (right)

Arthur Wheeler, GUARD

Philip King, BACK

Franklin Morse, BACK

1894— Langdon Lea, TACKLE

Arthur Wheeler, GUARD

1895— Langdon Lea, TACKLE

Dudley Riggs, GUARD

1896— William Church, TACKLE

Robert Gailey, CENTER

Addison Kelly, BACK

John Baird, BACK

1897— Garrett Cochran, END

Addison Kelly, BACK

1898— Lew Palmer, END (right)

Arthur Hillebrand, TACKLE

1899— Arthur Hillebrand, TACKLE

Arthur Poe, END

Howard Reiter, BACK

1901— Ralph Davis, END

1902— John DeWitt, GUARD (right)

1903— Howard Henry, END

John DeWitt, GUARD

Dana Kafer, BACK

1904— James Cooney, TACKLE

1905— James McCormick, BACK

1906— L . Casper Wister, END

James Cooney, TACKLE

Edward Dillon, BACK

1907— L . Casper Wister, END

Edwin Harlan, BACK

James McCormick, BACK (right)

1908— Frederick Tibbott, BACK

1910— Talbot Pendleton, BACK

1911— Sanford White, END

Edward Hart, TACKLE

Joseph Duff, GUARD

1912— John Logan, GUARD 1912— John Logan, GUARD

1913— Harold Ballin, TACKLE (right)

1914— Harold Ballin, TACKLE

1916— Frank Hogg, GUARD

1918— Frank Murrey, BACK

1920— Stan Keck, TACKLE (right)

Donold Lourie, BACK

1921— Stan Keck, GUARD

1922— C. Herbert Treat, TACKLE

1925— Ed McMillan, CENTER

1935— Jac Weller, GUARD

1951— Dick Kazmaier, BACK

1952— Frank McPhee, END

1965— Stas Maliszewski, GUARD

RUTGERS

1917— Paul Robeson, END (right)

1918— Paul Robeson, END

1961— Alex Kroll, CENTER

1995— Marco Battaglia, TIGHT END

|