|

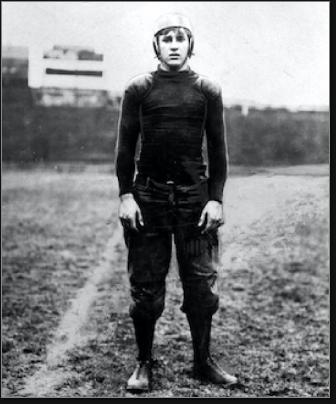

Harold Weekes

Sports: Football & Track

Born: April 2, 1880

Died: July 6, 1950

Town: Morristown

Harold Hathaway Weekes was born April 2, 1880 in Oyster Bay, Long Island and spent four years as a teenager in New Jersey at The Morristown School, a boarding school that later became the current-day Morristown-Beard School. A robust, quick-thinking young athlete, Harold grew up in a privileged environment, but was drawn to team sports such as baseball, football and ice hockey. He also excelled as a sprinter, at one point equaling the world indoor record in the 60-yard dash at 6.25 seconds. At Morristown, Harold distinguished himself as a game-changing halfback.

Harold entered Columbia University in the fall of 1899 and began the football season as a substitute end. He stood 5’10 and 175 pounds—a good size for that time—and it took first-year coach George Sanford a few weeks to realize he had a spectacular running back on his team. Once he did, he decided to keep Harold under wraps until Columbia’s meeting with Yale. The strategy paid off when he galloped 45 yards for a touchdown in a 5–0 win, bringing 5,000-plus Columbia fans to their feet. Harold was named a third-team All-American as a freshman.

As a sophomore, Harold invented a play called the Flying Hurdle (left). He would take a running start before the ball was snapped, receive the hand-off, and then use the back of the center—Bessie Bruce—as a springboard to leap over the tangle of bodies at the line. He tucked in his legs until he cleared the scrum and then landed ready to run. If a defensive player tried to stop him, he might expect a foot in the face. On defense, Harold’s job was to stop enemy ball carriers after they’d broken free for big gains, often chasing them down from behind. He was a second-team All-American as a sophomore

Most of Harold’s big gains for Columbia came around end. He was a patient runner who let his blocking develop and then exploded into another gear. His footwork in the open field left tacklers grasping at air. On defense, Harold had exceptional lateral mobility—john Heisman said he “slithered sideways like a fiddler crab.”

In the spring of his sophomore year, Harold participated in a strength competition of college athletes conducted at Harvard. He placed first in back and leg strength and fourth overall.

In his final two seasons of varsity football, Harold distinguished himself as the greatest player in school history—an honor he could still claim more than a quarter-century later. He was an All-American in 1901 and again as team captain in 1902. In the 1902 game against powerhouse Princeton, the Tigers tasked their star back, Dana Kafer, with stopping Harold's patented play. Kafer timed his run and leap perfectly, and the two men collided six feet in the air with such force that both ahd to be carted off the field. Following Harold's senior season, more than 600 students gathered to present him with an enormous silver loving cup.

While at Columbia, Harold rowed crew, played the outfield for the baseball team and destroyed almost all of the school’s sprinting records. His best time in the 100-yard dash was 10.15 seconds. Harold graduated in 1903 and coached the Kansas football team for one season. He then took a job as a stockbroker in New York.

Over the next two decades, he built the world’s foremost stamp collection, which he sold at the height of the Depression for $1 million. Harold passed away in 1950. Four years later he was inducted posthumously into the College Football Hall of Fame. In 1962, Harold was featured in Alex Weyand’s book, Football Immortals. Harold’s breathtaking home in Islip, Long Island was later converted into an environmental center.

|

|

|