|

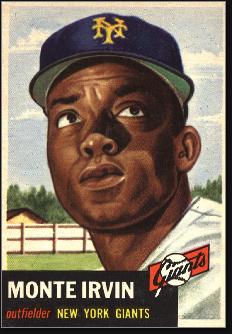

Monte Irvin

Sport: Baseball

Born: February 25, 1919

Died: January 11, 2016

Town: Orange

Monford Merrill Irvin was born February 25, 1919 in Haleburg, Alabama and grew up in Orange, New Jersey. One of 13 brothers and sisters, Monte moved north with his family to Orange in the mid-1920s. Among the extended family that made the trip north was his nephew, Harvey Grimsley, who would become a standou football player for Rutgers. He became a standout in baseball, football, basketball and track for East Orange High, earning four varsity letters in each of his four years. He stood 6’1” and was a rock-solid 190 pounds. His size, speed and quickness made him a demon on the football field, and his strong arm enabled him to set a schoolboy record in the javelin throw.

Harry Kipke, the University of Michigan’s legendary coach, wanted Irvin for his backfield. Unfortunately, even with a football scholarship, the Irvins did not have the money to send their son away. Instead, he attended Lincoln University, a historically black college in Pennsylvania. Monte’s plan was to use his football scholarship to earn a degree in dentistry, but when practice started to cut into his study time, he left the school and joined the Newark Eagles at the age of 19.

Two seasons earlier, Monte had played for the club under an assumed name, in order to maintain his amateur status. By 1940, Monte was the team’s everyday shortstop and best hitter. In 1941, he batted over .400, establishing himself as one of the best players in the Negro Leagues. Heading into 1942, Irvin was expecting a raise. When team owners Abe and Effa Manley turned him down, he accepted an offer to play in the Mexican League, for the Vera Cruz Blues. Despite missing the first quarter of the season, Monte still led the league in home runs and batting.

Monte was drafted in 1943 and served in the 1313th General Services Engineers, an all-African American unit tasked with infrastructure projects in England and (later) France and Belgium. He served until September 1945 and barely picked up a glove during that time.

Monte returned to Newark in the fall of 1945. He rejoined the Eagles for the tail end of the season and soon discovered that three years with no baseball had dulled his competitive edge. He sharpened his game in the Puerto Rican Winter League and was named MVP. In the spring of 1946, he returned to the Eagles and won the batting championship. That season, Monte teamed with second baseman Larry Doby and star pitcher Leon Day to lead the Eagles to the Negro National League pennant and a seven-game victory over the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro League World Series.

In 1947, Branch Rickey of the Brooklyn Dodgers showed interest in signing Monte. Because the Negro Leagues were not regarded as part of organized baseball, the Dodgers did not have to respect his contract with the Eagles. Effa Manley threatened to sue the Dodgers and Rickey backed off. Monte remained an Eagle for the 1947 and 1948 seasons. With the integration of the Major Leagues, the Negro National League folded and the Eagles went out of business. In 1947, Branch Rickey of the Brooklyn Dodgers showed interest in signing Monte. Because the Negro Leagues were not regarded as part of organized baseball, the Dodgers did not have to respect his contract with the Eagles. Effa Manley threatened to sue the Dodgers and Rickey backed off. Monte remained an Eagle for the 1947 and 1948 seasons. With the integration of the Major Leagues, the Negro National League folded and the Eagles went out of business.

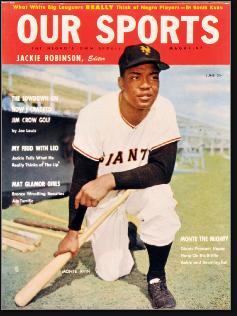

In 1949, after Monte led the Cuban Winter League in home runs, the New York Giants signed him. He hit .224 as a 31-year-old “rookie” in limited action. He became a regular in 1950, and in 1951 led the Giants with a .312 batting average and was the NL leader with 121 runs batted in. He finished third in the MVP voting, behind Roy Campanella and Stan Musial.

The Giants made headlines that year by winning the pennant on Bobby Thomson’s 9th-inning home run against the Brooklyn Dodgers. Two days later, Monte joined Willie Mays and Hank Thompson in Game 1 of the World Series to form the first all-black outfield in big-league history. Monte batted .458 in the series against the Yankees, but the Giants fell 4 games to 2.

Monte played four more years with the Giants. During that time, he served as a mentor to Mays, and also helped the Giants win the 1954 World Series. During the 1955 season, the Giants sent Monte to the minors. The Chicago Cubs snapped him up in 1956 and he hit 15 homers and batted .271 in his final big-league season. He hung up his spikes after injuring his back during spring training with the minor-league Los Angeles Angels in 1957.

Monte got a community relations job with Rheingold Beer, a favorite of blue-collar fans, both white and black. Rheingold was one of the Mets’ first sponsors when NL baseball returned to New York in 1962. Monte developed a close relationship with the club and, in 1967, left Rheingold to scout for the Mets. In 1968, he was hired by Major League Baseball as a public relations specialists, making him MLB’s first African-American executive. He retired as a fulltime executive in 1984, but continued to work on special projects for MLB.

Monte was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1973, voted in by a special committee for his exploits as a Negro Leaguer. In 2010, the Giants retired his number 20 and, that fall, he threw out the first pitch before one of the team’s World Series games. He passed away in 2016 at the age of 96 in Houston.

Monte’s big-league numbers were 99 homers, 443 RBIs and a .293 average in 764 games—all achieved in his declining years as an athlete. What might his record look like had the playing field been even when he entered the game? Most experts put him in the same class statistically with players like Al Kaline, Billy Williams and Jim Rice. But everyone who knew Monte Irvin knew that was only half the answer. He was truly in a class by himself.

|

|

|