BASEBALL in New Jersey

The definitive history. The definitive history.

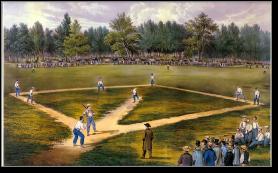

If you believe the old story, organized baseball “started” in New Jersey in 1846. On June 19th the Knickerbocker Club played the New York Nine in Hoboken. The two clubs met for what many consider to be the first official game between two teams. They played at Elysian Fields, a wide expanse of green across the Hudson from downtown New York. The Knickerbockers had been using the field for a year for their baseball playing, but this marked the first time they competed against another club. Somewhat ironically, the New York Nine included several former Knickerbockers who had quit the club because they objected to traveling so far to play baseball. The organizer of the game was Alexander Cartwright, regarded by many as the Father of Baseball.

The spot in Hoboken was perfect for baseball—a large, flat ground reachable with minimal effort and expense from New York City. In the 1860s, baseball games at the Elysian Fields drew crowds of 10,000 or more. It was also a favorite for cricket matches. At the time, cricket was still the more popular sport among adults. However, baseball was closing the gap. It evolved from an assortment of 18th century children’s games and was widely played by adults by the 1830s. In 1831, a group of young men from Philadelphia met regularly across the river, in Camden, to play Townball. This pastime was similar to baseball, but was played on a square field, with the batter located between the first and fourth base. Townball persisted for several decades in New Jersey and, especially, in New England, where it was known as the “Massachusetts Game.” The "New York Game" played by the Knickerbockers eventually won out; Base-Ball (as it was often written in the 1800s) was more fun to play and more interesting to watch.

The firstbaseball teams sprang from groups of men who were linked professionally or socially. A club of bank clerks or engineers might field a team. Many fire companies played baseball to pass the time between blazes.

The first official teams in New Jersey were formed in the mid-1850s. The earliest came from Newark and Jersey City. A team called the Fear Nots played in Hudson City, which later became Jersey City Heights. By the end of the decade there were active club teams in Elizabeth, Hoboken, New Brunswick, Orange, Princeton, Somerville and Trenton. In the 1860s, clubs were formed in Belvidere, Bergen, Camden, Englewood, Irvington, Paterson and Rahway. The first official teams in New Jersey were formed in the mid-1850s. The earliest came from Newark and Jersey City. A team called the Fear Nots played in Hudson City, which later became Jersey City Heights. By the end of the decade there were active club teams in Elizabeth, Hoboken, New Brunswick, Orange, Princeton, Somerville and Trenton. In the 1860s, clubs were formed in Belvidere, Bergen, Camden, Englewood, Irvington, Paterson and Rahway.

As mid-19th century travel tended to be time-consuming and expensive, most of the ball-playing was done among club members. However, when two did meet it was quite an event. The contest would be part of an entire day of activities, including an extravagant dinner. In these games, the best players did not always man the most important positions. The more senior club members got to choose where they fielded and batted. The games were competitive, but not in the modern sense. “Hard-nosed” baseball would not come until after the Civil War.

In 1857, 16 of the nation’s strongest baseball clubs banded together to form the National Association of Base Ball Players. When member clubs competed they abided by the same set or rules and conduct. In 1858, the association welcomed its first New Jersey team, the Liberty Club of New Brunswick. In 1859, a club from Trenton joined. Between 1860 and 1870, several clubs from Newark joined the NABBP, including the Eurekas, Adriatics, Americus, Excelsiors, and Actives.

College baseball gained an important foothold during the years of the Civil War. Many students at northern schools delayed their participation in the military until after graduation, or avoided it altogether. This enabled baseball clubs to play and practice together at a time when other amateur teams often could not. The Nassau Baseball Club at Princeton University (then the College of New Jersey) became something of a juggernaut. A student named L.W. Mudge—who had gained some renown as a ball player in his native Brooklyn—whipped the Nassau nine into shape with the help of some fellow Brooklynites and soon they were playing, and beating, the top clubs in New York, New Jersey and Phialdelphia. In September 1863, they won three of four games against Brooklyn's best, defeating Excelsiors, Stars and Resolutes, while falling to the Atlantics.

During the 1850s and 1860s, some baseball clubs were known to compensate their best players. Sometimes the payment was made in cash, other times in goods or services. By the end of the 1860s, “professionalism” had become common. Baseball had changed. Soldiers returning from the life-and-death struggle of the war craved action and excitement. They played to win, and the best base-ballers expected to be paid for their services. Very rapidly, there was a separation between the amateur clubs that clung to the old ways, and “teams” that charged admission (or at least passed the hat) at their games.

New Jersey’s first all-professional baseball team was the Elizabeth Resolutes. They competed for one season (1873) in the National Association of Professional Baseball Players. The Association operated from 1871 to 1875. It was the country’s first pro league, with teams from New England to the Midwest. The Association was structured to favor professional ball players, and was a precursor  to the National League, which formed in 1876 and still operates today. The National League was formed to serve the interests of baseball owners. to the National League, which formed in 1876 and still operates today. The National League was formed to serve the interests of baseball owners.

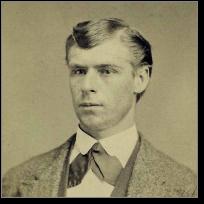

The Resolutes played just 23 league games, and lost 21 before folding. Their manager and catcher was Doug Allison (right), a player largely forgotten by history. In his time he was very famous. Allison was the catcher on the famous 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings, who helped to popularize baseball after the Civil War. Allison was the first player to “perfect” the skills demanded of the catcher. Prior to that, catcher was regarded as a place an exhausted or injured player could rest.

The pro team with the most staying power was the Jersey City Skeeters. The club formed around the time of the Civil War and played on and off in various minor leagues until the Depression. The Skeeters were named after the infernal bugs that rose in clouds from the New Jersey swamps. In 1903, the Skeeters won their first 18 games and went on to cop the Eastern League crown. It was a fitting Thank You to the town, which had constructed a new baseball stadium for them the year before.

The best baseball being played in New Jersey during the late 1800s and early 1900s may have been on the college level. Princeton formed its first baseball team in 1858, making it the school’s oldest organized sport. Its first intercollegiate match was against Williams College in 1864. The Tigers’ first star was Joe Mann. He mastered the curve ball after receiving a lesson from professional star Candy Cummings—and used it to no-hit Yale in 1875. Another Princeton innovator was Bill Schenck. In an 1880 game against Harvard the catcher stuffed copies of the Princetonian under his uniform to help absorb the impact of foul tips. It was one of the first recorded uses of a chest protector.

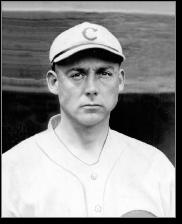

Princeton’s first full-time baseball coach was Boileryard Clarke (left), the catcher on the great Baltimore Oriole teams of the 1890s. Though few Princeton players went on to play professionally (pro baseball was considered unsuitable for educated men), one who did was Moe Berg. Berg was a so-so catcher during 15 years in the majors; Casey Stengel once said, “Berg could speak eight languages but couldn’t hit in any of ’em.” Nevertheless, he was a member of a 1934 All-Star team that toured Japan. His “home movies” of Tokyo harbor and its factories were later used to plan bombing raids during World War II. Berg also did some spying for the U.S. government in Switzerland during the war. Princeton’s first full-time baseball coach was Boileryard Clarke (left), the catcher on the great Baltimore Oriole teams of the 1890s. Though few Princeton players went on to play professionally (pro baseball was considered unsuitable for educated men), one who did was Moe Berg. Berg was a so-so catcher during 15 years in the majors; Casey Stengel once said, “Berg could speak eight languages but couldn’t hit in any of ’em.” Nevertheless, he was a member of a 1934 All-Star team that toured Japan. His “home movies” of Tokyo harbor and its factories were later used to plan bombing raids during World War II. Berg also did some spying for the U.S. government in Switzerland during the war.

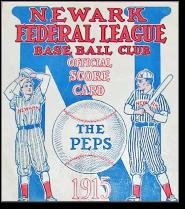

In 1915, New Jersey finally got its first “major league” team, the Newark Peppers. They played exactly one year during the final season of the Federal League, an upstart circuit that competed with the National and American Leagues. The Peppers were owned by Harry Sinclair, an Oklahoma oil baron who wanted to start a team in New York City. The roster was made up of players from the previous year’s Federal League champions, the Indianapolis Hoosiers. The plan was to win the 1915 pennant, move across the Hudson, and then outdraw the Yankees, Giants and Dodgers. In 1915, New Jersey finally got its first “major league” team, the Newark Peppers. They played exactly one year during the final season of the Federal League, an upstart circuit that competed with the National and American Leagues. The Peppers were owned by Harry Sinclair, an Oklahoma oil baron who wanted to start a team in New York City. The roster was made up of players from the previous year’s Federal League champions, the Indianapolis Hoosiers. The plan was to win the 1915 pennant, move across the Hudson, and then outdraw the Yankees, Giants and Dodgers.

Sinclair was one of the richest men in America, and for that single season a hands- on owner in the mold of George Steinbrenner. Though he only planned to stay in New Jersey for a year, Sinclair had a brand new stadium constructed across the Passaic River in Harrison, within walking distance of downtown Newark. He offered John McGraw the unheard-of sum of $100,000 to leave the Giants and become his manager. McGraw turned him down. Nonetheless, the Peppers opened their season to a standing room only crowd. The team featured two future Hall of Famers, Edd Roush (left) and Bill McKechnie. Germany Schaefer, a crowd-pleasing veteran, was also on the team. The pitching staff was led by Ed Reulbach, one of the best players not in the Hall of Fame. Sinclair was one of the richest men in America, and for that single season a hands- on owner in the mold of George Steinbrenner. Though he only planned to stay in New Jersey for a year, Sinclair had a brand new stadium constructed across the Passaic River in Harrison, within walking distance of downtown Newark. He offered John McGraw the unheard-of sum of $100,000 to leave the Giants and become his manager. McGraw turned him down. Nonetheless, the Peppers opened their season to a standing room only crowd. The team featured two future Hall of Famers, Edd Roush (left) and Bill McKechnie. Germany Schaefer, a crowd-pleasing veteran, was also on the team. The pitching staff was led by Ed Reulbach, one of the best players not in the Hall of Fame.

Despite all of this talent, the Peppers finished in fifth place. The Federal League went out of business after the season. In the final days of the league, Sinclair (right), a brilliant businessman, used his money and power to gobble up anything of value (most notably player contracts) and was probably the only person to turn a profit on the Federal League adventure. He briefly toyed with the idea of buying the Giants, but decided to stick to oil wells and returned to Oklahoma. As for Newark, it not only lost the Peppers but also the Indians, an International League team. Sinclair’s aggressive promotions convinced them to move to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The Indians had been league champions just two seasons earlier. Despite all of this talent, the Peppers finished in fifth place. The Federal League went out of business after the season. In the final days of the league, Sinclair (right), a brilliant businessman, used his money and power to gobble up anything of value (most notably player contracts) and was probably the only person to turn a profit on the Federal League adventure. He briefly toyed with the idea of buying the Giants, but decided to stick to oil wells and returned to Oklahoma. As for Newark, it not only lost the Peppers but also the Indians, an International League team. Sinclair’s aggressive promotions convinced them to move to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The Indians had been league champions just two seasons earlier.

After the Federal League left New Jersey, the top tier of organized baseball in the Garden State was the International League—which returned to Jersey City in 1918 and to Newark in 1926. The Jersey City team did not survive the Depression, but the Newark Bears thrived as the top farm team of the Yankees. Playing their home games at Ruppert Stadium in the current-day Ironbound section of the city, the Bears won the IL pennant seven times between 1932 and 1942, topping 100 victories five times. The 1937 club is considered one of the best minor-league teams ever.

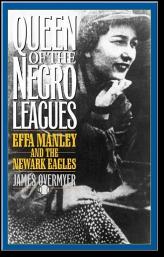

Ironically, the 1937 Bears might not have been the best team in Newark—or even in their own stadium! One year earlier, two Negro League teams—the Newark Dodgers and Brooklyn Eagles—merged to create the Newark Eagles. The Eagles were owned and operated by Effa Manley, the first woman to serve in this dual capacity for a professional sports team. She later became the first woman inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. When the Bears were on the road, the Eagles—who barnstormed in addition to playing league games—would play their home games in Ruppert Stadium. The 1937 Eagles featured the “Million Dollar Infield” of Ray Dandridge, Willie Wells, Dick Seay and Mule Suttles. The outfield starred Jimmie Crutchfield and the pitching staff was anchored by Speed McDuffie and Leon Day. Ironically, the 1937 Bears might not have been the best team in Newark—or even in their own stadium! One year earlier, two Negro League teams—the Newark Dodgers and Brooklyn Eagles—merged to create the Newark Eagles. The Eagles were owned and operated by Effa Manley, the first woman to serve in this dual capacity for a professional sports team. She later became the first woman inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. When the Bears were on the road, the Eagles—who barnstormed in addition to playing league games—would play their home games in Ruppert Stadium. The 1937 Eagles featured the “Million Dollar Infield” of Ray Dandridge, Willie Wells, Dick Seay and Mule Suttles. The outfield starred Jimmie Crutchfield and the pitching staff was anchored by Speed McDuffie and Leon Day.

New Jersey did see major league ball again, in 1956 and 1957. The Brooklyn Dodgers played one “home game” against each of the other seven National League teams in the Garden State during those seasons. The venue was Roosevelt Stadium, which opened in Jersey City in 1937. Roosevelt Stadium was home to the International League’s Jersey City Giants until 1950, and then served as home field for farm teams of the Reds (1960 & 1961), Indians (1977) and A’s (1978).

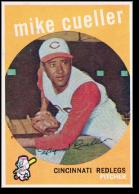

When the Reds were tenants, the team (called the Jersey City Jerseys) featured some of the top young Latino stars of the day, including Mike Cuellar, Cookie Rojas, Chico Cardenas, Vic Davalillo and Julian Javier. The Jerseys had previously played in Havana as the Sugar Kings, but were hastily relocated by the Reds organization after Fidel Castro nationalized American-owned businesses in Cuba. The most famous baseball event in Roosevelt Stadium occurred in 1946, when Jackie Robinson played his first game as a member of the Montreal Royals—one year before breaking the color barrier with the Dodgers. When the Reds were tenants, the team (called the Jersey City Jerseys) featured some of the top young Latino stars of the day, including Mike Cuellar, Cookie Rojas, Chico Cardenas, Vic Davalillo and Julian Javier. The Jerseys had previously played in Havana as the Sugar Kings, but were hastily relocated by the Reds organization after Fidel Castro nationalized American-owned businesses in Cuba. The most famous baseball event in Roosevelt Stadium occurred in 1946, when Jackie Robinson played his first game as a member of the Montreal Royals—one year before breaking the color barrier with the Dodgers.

By the 1960s, pro baseball had become a more acceptable occupation for a college grad, and New Jersey’s institutions of higher learning produced some good ones over the next 50 years, including Jeff Torborg, Eric Young and David DeJesus (Rutgers), Chris Young and Will Venable (Princeton), Ed Halicki (Monmouth College), Al Downing and Jack Armstrong (Rider College), Mark Leiter (Ramapo College), and Johnny Briggs, Rick Cerone, Craig Biggio, Mo Vaughn, John Valentin and Matt Morris (Seton Hall).Brookdale, a community college in Monmouth County, produced John Montefusco, who went on to be named NL Rookie of the Year.

During the 1970s and 1980s, minor league baseball went into a period of decline. Its revival began in the 1990s. From 1994 through 2002, the St. Louis Cardinals operated a farm team in Skylands Park in Augusta, in the northwest corner of the state. They were followed by the Sussex Skyhawks, who played in Augusta from 2006 through 2010.

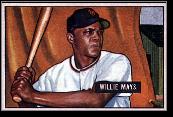

In 1994, the Detroit Tigers moved their Eastern League farm team to Trenton and renamed it the Thunder. The Thunder later became affiliated with the Red Sox and  Yankees. Trenton quickly became one of the great success stories of minor league baseball, drawing more than 500,000 fans a season several times. Trenton had been without pro baseball for nearly 50 years after having hosted minor-league clubs dating back as far as the 1880s. In 1950, Trenton’s final season as a farm club of the Giants, Willie Mays (left) played center field for the team. In one famous game, he made a barehanded catch to rob an enemy hitter of a home run. Mays often said it was the best defensive play he ever made. Yankees. Trenton quickly became one of the great success stories of minor league baseball, drawing more than 500,000 fans a season several times. Trenton had been without pro baseball for nearly 50 years after having hosted minor-league clubs dating back as far as the 1880s. In 1950, Trenton’s final season as a farm club of the Giants, Willie Mays (left) played center field for the team. In one famous game, he made a barehanded catch to rob an enemy hitter of a home run. Mays often said it was the best defensive play he ever made.

In the late 1990s, two independent minor league franchises moved into New Jersey stadiums. The New Jersey Jackals play in Little Falls and the Newark Bears play in downtown Newark. The Jackals won the Northern League championship in 1998, 2001, 2002 and 2004. The Bears, who borrowed the name of the city’s famous team of the 1930s and 40s, played their inaugural season in 1999. Both teams struggled financially. The team in Newark did not take the field for the 2014 season and eventually went out of business, leaving their new stadium to go to seed.

The Phillies had better luck in the Garden State. In 2001, they moved their Class-A minor league team from North Carolina to Lakewood and renamed them the Blue Claws. Playing in a family-friendly stadium, the team consistently drew sellout crowds regardless of their performance on the field. That being said, there was never a lack of talent on the club. The first Blue Claw to reach the majors was Ryan Howard (right). He was named National League Rookie of the Year in 2005 and Most Valuable Player in 2006.

The 2016 season marked a milestone in New Jersey baseball history. Mike Trout of Millville—the first NJ-born player to win the AL MVP award—was honored for the second time, along with Rick Porcello of Morristown, who was named the AL Cy Young Award winner. It was the first AL Cy Young for a NJ-born player, and obviously the first time a pair of New Jerseyans won major baseball awards in the same season.

BASEBALL ALL-STARS BORN IN NEW JERSEY

• Click on a name to read a bio... • Click on a name to read a bio...

Jack Armstrong (Englewood) 1990

Andrew Bailey (Voorhees) 2009–10

Hank Borowy (Bloomfield) 1944

Jim Bouton (Newark) 1963

Brad Brach (Freehold) 2016

George Case (Trenton) 1939, 1943-44 Doc Cramer

Sean Casey (Willingboro) 1999, 2001 & 2004

Doc Cramer (Beach Haven) 1935 & 1937-40

Joe Cunningham (Paterson) 1959 (1 & 2)

Al Downing (Trenton)) 1967

Todd Frazier (Point Pleasant) 2014–15

Goose Goslin (Salem) 1936

Jeffrey Hammonds (Plainfield) 2000

Erik Hanson (Kinnelon) 1995

Frankie Hayes (Jamesburg) 1939-41, 1944 & 1946

Jason Heyward (Ridgewood) 2010

Derek Jeter (Pequannock) 1998-2002, 2004 & 2006-12 & 2014 Joe Medwick

Billy Johnson (Montclair) 1947

Eddie Kasko (Linden) 1961 (1 & 2)

Johnny Kucks (Hoboken) 1956

Al Leiter (Toms River) 1996 & 2000

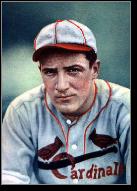

Joe Medwick (Carteret) 1934-42 & 1944

Andy Messersmith (Toms River) 1971 & 1974-76

John Montefusco (Long Branch) 1976

Ray Narleski (Camden) 1956 & 1958

Don Newcombe (Madison) 1949-51 & 1955

Jose Rosado (Newark) 1997 & 1999

Johnny Romano (Paterson) 1961 (1 & 2) & 1962 (1 & 2)

Hector Santiago (Newark) 2015 Johnny Vander Meer

Eddie Smith (Mansfield) 1941–42

Mike Trout (Millville) 2011–18

Hal Wagner (East Riverton) 1942 & 1946

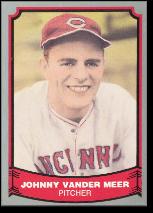

Johnny Vander Meer (Prospect Park) 1938-39 & 1942-43

Eric Young (New Brunswick) 1996

Frankie Zak (Passaic) 1944

|