It Happened in Jersey: Boxing & Wrestling

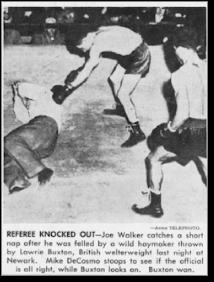

Decision By Knockout

Most old-time New Jersey sports fans know that one of the state’s great boxing products was world welterweight champion Mickey Walker. What many do not know is that his brother, Joe, was a boxing referee. The Walkers were originally from Elizabeth, which was a hotbed of boxing well into the 1950s, and Joe did much of his work there and in Newark. On a spring night in 1948, Joe Walker was involved in one of the most bizarre conclusions to a bout in prizefighting history.

The fight, a 10-rounder between Englishman Lawrie Buxton and Elizabeth’s Mike DeCosmo, took place at the Meadowbrook Bowl in Newark. It marked the opening of the outdoor season at the arena, but the mercury had dipped into the 40’s when the preliminaries began and few fans stayed until the feature bout. Those who did witnessed an entertaining and closely contested fight between the European veteran and the left-handed local. Entering the 10th round, most people scoring the fight had it dead even, meaning whoever landed the most blows in the final three minutes would be declared the winner. And indeed, Walker had the score knotted 4–4–1.

By state rules at the time, if both fighters were still standing at the end of the last round, it was up to the referee to declare a winner. DeCosmo—known for throwing haymakers—poured it on in the closing seconds, desperate to outscore the more tactical Buxton. After the bell rang the two combatants were still throwing punches, so Walker stepped in. At which point Buxton landed his best poke of the evening—right to the jaw of the referee, who went down like a tree, out cold.

It took several minutes to revive Walker, who was immediately asked who won the fight. Everyone in the arena knew the answer: clearly it was DeCosmo. However, Walker assumed the kayo blow had come from the wild-swinging DeCosmo and he wasn’t about to let the southpaw celebrate a decision and a knockout at the same time. The crowd rained boos down on the referee when he proclaimed Buxton the winner.

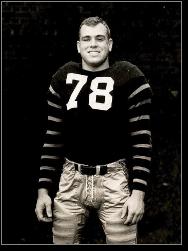

HEART OF GLASS HEART OF GLASS

During the 1950s, Bradley Glass was Princeton’s BMOC—literally. Brad was a two-way guard on the Tigers’ unbeaten 1950 national champion football team as a sophomore, earning All-America recognition. That winter, he won the Eastern Intercollegiate Association heavyweight wrestling title, defeating Penn State’s Homer Barr, and went on to the NCAA championships in Bethlehem. There he defeated Barr in the finals again to become Princeton’s one and only national champion in the sport.

Brad repeated as EIWA champion in 1952 and finished third in the NCAA tournament, earning All-America honors in his second sport. He tried out,  unsuccessfully, for the US Olympic team. He graduated in 1953, with three varsity football letters. The Tigers lost one game during his three seasons as a starter. unsuccessfully, for the US Olympic team. He graduated in 1953, with three varsity football letters. The Tigers lost one game during his three seasons as a starter.

After graduation, Brad joined the Navy and was part of the underwater demolition group that later became known as the Seals. He tried again in 1956 to make the Olympic wrestling squad, while still serving in the Navy, but fell short. He was named an alternate.

After Brad’s time in the service, while studying law at the University of Michigan, he served as an assistant on the wrestling team. He eventually returned to his home state of Illinois. (As a high school wrestler in Winnetka, he had been a teammate of Donald Rumsfeld’s and was the state heavyweight champ in 1947.) Brad focused on his law career, founding his own practice and serving as a state senator during the 1970s. In 2001, Brad was inducted into the Eastern Wrestling Hall of Fame. He passed away in 2015.

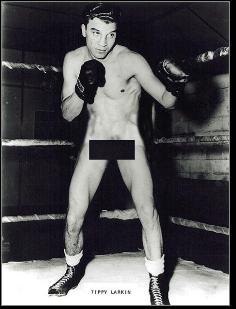

OH, BROTHER

Jack and Sammy Amato, brothers from Garfield born just over a century ago, both loved to box as boys. In 1926, Jack enlisted in the Navy at age 15, lying about his date of birth. Serving with the Mediterranean Fleet, he fought for the fleet’s welterweight title until he was discharged in 1928, after it was discovered that he was still underage.

By then, Sammy had started his boxing career. Jack accompanied him to an event near their home, at the old Belmont Park. Hanging outside the dressing room prior to Sammy’s bout, Jack overheard the promoter ask if there were any 147-pounders who would like to step in the ring. Jack stepped up and agreed to fight—only to learn his opponent would be his brother.

Jack changed his name on the spot to Jack Larkin and the brothers faced each other in the ring for the first of 22 times! Jack became an influential boxing manager in New Jersey and, as a fighter, was crowned middleweight champion of Bergen County. During the 1940s and 50s, he operated out of Stillman’s Gym in New York. One of his fighters, Tippy Larkin (to whom he gifted his “family name”), became world Junior Welterweight Champion.

UM, FORGET SOMETHING?

Tippy Larkin (born Tony Pilliteri) was known as The Garfield Gunner. He also was known as an intense fighter. His focus and mental preparation in the minutes leading up to a bout was legendary. On January 12, 1942, he was scheduled to meet Tommy Cross in Newark.

The fighters were introduced to the crowd, each taking a few steps toward the center and raising a glove to acknowledge the cheers. When Tippy returned to his corner to await the opening bell, he slipped off his robe to shrieks of laughter.

He had forgotten to pull his trunks on before leaving the locker room and was completely naked save for his socks and shoes.

|