SOCCER in New Jersey

The definitive history. The definitive history.

The earliest soccer games played in New Jersey took place in the years following the Civil War. The game called “football” had been imported by students and immigrants from the British Isles, where it had a long and violent history. The game back then amounted to little more than organized mayhem. Players were allowed to use their hands and there was little in the way or skilled dribbling, passing or shooting.

Tackling was allowed—not soccer tackling, but football tackling. The famous first intercollegiate football game played between Princeton and Rutgers in 1869 could just as well have been called the first college soccer game, too.

Across the Atlantic, football was evolving into two different sports—the carrying game, also known as rugby, and the kicking game, which came to be known as soccer. By the mid-1870s, the top American universities had started to adopt the kicking game, and by the 1880s its transformation into American football was well under way, thanks to pioneers like Walter Camp. Soccer was a casualty in this scenario; the country’s future leaders and powerbrokers had committed to football, and at most schools soccer was dropped as a fall sport. Across the Atlantic, football was evolving into two different sports—the carrying game, also known as rugby, and the kicking game, which came to be known as soccer. By the mid-1870s, the top American universities had started to adopt the kicking game, and by the 1880s its transformation into American football was well under way, thanks to pioneers like Walter Camp. Soccer was a casualty in this scenario; the country’s future leaders and powerbrokers had committed to football, and at most schools soccer was dropped as a fall sport.

The game did not die in the United States. On the contrary, Irish, Scot and English immigrants who came to the U.S. in the late 1800s kept the game very much alive. In their communities along the East Coast—in working-class enclaves like Fall River, Massachusetts and Kearny, New Jersey—the game was immensely popular. Soccer in Kearny got a huge boost after the Clark Thread Company expanded operations there and brought over hundreds of workers from its plant in Paisley, Scotland. In Paterson, the silk business was booming in the 1870s. As more workers experienced in this industry emigrated across the Atlantic, soccer in this city became very popular, too.

In 1885, the American Football Challenge Cup tournament began. The first champion was the Clark-backed ONT of Kearny (ONT was short for Our New Thread, Clark’s new product). The Kearnyy club defeated New York FC in the title game, and then went on a tour of Canada, winning 9 of 11 matches and drawing one. A team of Canadian stars returned the favor, touring the New York Metro area in the fall of that year. On November 25, the Canadian stars met a hand-picked team of American stars at the Clark field in Kearny. The Canadians won 1–0. It was the first international soccer match played by a U.S. team.

The Clark factory club won the next two “American Cups.” They beat the cross-town Kearny Rangers both times. In the years that followed, soccer continued to grow in popularity in New Jersey. However, control of the Challenge Cup shifted to the great teams from Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Not until 1896, when the Paterson True Blues won, did the American Cup return to the Garden State. The Clark factory club won the next two “American Cups.” They beat the cross-town Kearny Rangers both times. In the years that followed, soccer continued to grow in popularity in New Jersey. However, control of the Challenge Cup shifted to the great teams from Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Not until 1896, when the Paterson True Blues won, did the American Cup return to the Garden State.

By then some interesting developments had occurred in soccer. The National Association of Football Clubs was formed in 1895. Among its original teams were the Kearny Scots. This attempt to organized the country’s soccer clubs followed the first stab at introducing pro soccer to American sports fans. In 1894, the owners of National League baseball clubs, interested in keeping the turnstiles clicking after baseball season, were intrigued by the large and enthusiastic crowds they saw at local soccer games. In their eyes, soccer was an inexpensive spectacle to stage— there was virtually no equipment to purchase or maintain, and the top players only made a few dollars a game.

The American League of Professional Football was formed with teams in Baltimore, Boston, Brooklyn, New York, Philadelphia and Washington. They played league games against one another, as well as competing against the best local clubs. The New York Giants (all of the ALPF teams were named after their diamond counterparts) signed two of the top players in New Jersey, Hugh McGee and Alf Cutler. A day before the season’s first game, they quit the team, deciding to play instead for the Union Club of Kearny. The owner of the Giants was outraged—he announced that they would never player pro soccer again. Of course, McGee and Cutler were still playing for pay long after the ALPF folded. The league only lasted a few weeks, and attempts to revive it in 1895 were unsuccessful.

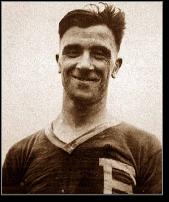

From the turn of the century to World War I, soccer thrived in New Jersey. Garden State teams reached the American Cup finals or won the Cup almost every year. Across the Hudson, in New York City and Westchester, soccer was also growing. Cross-river matches heightened the excitement surrounding the sport. The most exciting player during this time was Glasgow-born Archie Stark (left), a prodigious scorer who started his pro career at age 14 with the Kearney Scots. His goal in the 1915 American Cup final gave the Scots a 1–0 win over Brooklyn Celtic. In 1916, Stark took his talents to Bayonne, where he starred for the club backed by Babcock & Wilcox, a company that made industrial boilers (and today builds nuclear power plants). From the turn of the century to World War I, soccer thrived in New Jersey. Garden State teams reached the American Cup finals or won the Cup almost every year. Across the Hudson, in New York City and Westchester, soccer was also growing. Cross-river matches heightened the excitement surrounding the sport. The most exciting player during this time was Glasgow-born Archie Stark (left), a prodigious scorer who started his pro career at age 14 with the Kearney Scots. His goal in the 1915 American Cup final gave the Scots a 1–0 win over Brooklyn Celtic. In 1916, Stark took his talents to Bayonne, where he starred for the club backed by Babcock & Wilcox, a company that made industrial boilers (and today builds nuclear power plants).

In 1913, the U.S. Football Association was formed, and was recognized by FIFA, the sport’s international governing body. FIFA sanctioned a second championship tournament, the National Challenge Cup, which later became the US Open Cup.

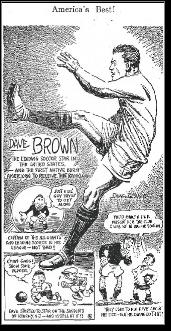

The first successful attempt at a pro soccer league came in the early 1920s, wi th the formation of the American Soccer League. It featured the country’s strongest clubs, including the Jersey City Celtics and Harrison FC. The 1920s were the Golden Age of Sports and although pro soccer is rarely mentioned in stories of this era, it was second to baseball in terms of popularity among professional team sports. The top American-born player during this time was Davey Brown, a Kearny native. Matches held in New Jersey often drew 5,000 or more paying fans. The crowds were even larger in New England. The players were paid well for their work, and the league grew in popularity and influence until the Great Depression. In 1922, a ladies all-star team from England played and lost to the men of Paterson FC. This match was likely the first instance of organized women’s soccer in New Jersey. th the formation of the American Soccer League. It featured the country’s strongest clubs, including the Jersey City Celtics and Harrison FC. The 1920s were the Golden Age of Sports and although pro soccer is rarely mentioned in stories of this era, it was second to baseball in terms of popularity among professional team sports. The top American-born player during this time was Davey Brown, a Kearny native. Matches held in New Jersey often drew 5,000 or more paying fans. The crowds were even larger in New England. The players were paid well for their work, and the league grew in popularity and influence until the Great Depression. In 1922, a ladies all-star team from England played and lost to the men of Paterson FC. This match was likely the first instance of organized women’s soccer in New Jersey.

As soccer grew more popular and profitable in the 1920s, the American Soccer League and United States Soccer Federation began fighting over control of the sport. Because the ASL represented professional clubs, its influence waned during the Great Depression, as teams struggled to stay afloat. In 1933, the ASL went out of business. It was soon replaced by a new American Soccer League. This was a far less ambitious organization; its teams were typically semipro and ethnic-based as opposed to fully professional. In the new ASL, which was based in the New York Metro during the 1930s, the Kearney Scots found themselves at the top of the heap. In the years following World War II, the ASL expanded and even arranged for top clubs from Europe and Great Britain to play exhibition matches in the United States. Before the advent of international television, these games were the only chance U.S. soccer fans had to witness world-class soccer.

In the early 1960s, New Jersey soccer fans got a steady diet of top soccer talent thanks to a new venture called the International Soccer League. The ISL featured U.S.-based teams as well as European clubs, which would participate in league games for a month or so. The European clubs saw it as an exhibition tune-up. Many of the matches were played at Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City. These events drew as many as 10,000 fans. Also during this era, New Jersey-based semipro clubs (originating from Hoboken and Elizabeth) traveled to West Germany for exhibition tours.

Soccer in the New York Metro area seemed poised to explode after huge TV ratings for the 1966 World Cup final convinced the U.S. Soccer Federation to sanction a new professional league. However, the turmoil and power struggles that ensued had precisely the opposite effect. At one point the ASL had only one team in New Jersey.

Things began to turn around in the years following Pele’s arrival with the New York Cosmos of the North American Soccer League. The Brazilian star reignited interest in soccer in the region, both from a spectator standpoint and also from a participation standpoint. For New Jersey, the big moment in came in 1977, when the Cosmos moved into the Meadowlands in East Rutherford.

Joining Pele (right) were Italian star Giogrio Chinaglia, Carlos Alberto of Brazil, and superstar sweeper Franz Beckenbauer, captain of West Germany’s World Cup team. A June meeting with the Tampa Bay Rowdies set a new U.S. record for attendance, drawing more than 62,000 fans. Pele scored all three goals in a 3–0 victory. The Cosmos averaged 34,000 fans per game in Giants Stadium and went on to win the NASL championship. Joining Pele (right) were Italian star Giogrio Chinaglia, Carlos Alberto of Brazil, and superstar sweeper Franz Beckenbauer, captain of West Germany’s World Cup team. A June meeting with the Tampa Bay Rowdies set a new U.S. record for attendance, drawing more than 62,000 fans. Pele scored all three goals in a 3–0 victory. The Cosmos averaged 34,000 fans per game in Giants Stadium and went on to win the NASL championship.

On October 1, 1977, Pele played his “farewell’ match before a capacity crowd at Giants Stadium. He played the first half wearing a Cosmos jersey against Brazil’s national team. He scored a goal on a free kick. At halftime the Cosmos retired Pele’s uniform. He finished the match playing for Brazil. When the final whistle sounded, the Cosmos lifted Pele onto their shoulders and carried him around the field.

The Cosmos won the NASL title again in 1980. The New Jersey-based team had become an international drawing card by this time, despite the fact they clung to their New York name. The team made numerous exhibition trips overseas. They defeated some of the world’s best clubs, including Manchester City, Santos and FC Cologne.

The law of gravity seized pro soccer in New Jersey during the early 1980s. The Cosmos won another championship in 1982, but their attendance began to sag. Worse, the NASL was in trouble. In trying to compete for big-name players, the smaller-market clubs overextended themselves and were covered in red ink. The league folded after the 1984 season.

Fortunately, the soccer fever that had gripped the Garden State in the 1970s had already begun to pay dividends. Participation in youth soccer programs was at an all-time high, and the state was producing top-notch players at the high school and college levels. In 1994, the United States hosted its first World Cup. Three members of the national team that year—Tab Ramos, John Harkes and Tony Meola—were from New Jersey.

New Jersey college soccer also began to flourish in the 1980s and 1990s, particularly on the men’s side of the game. In 1990, Rutgers advanced all the way to the NCAA final. Alexei Lalas and Steve Rammell were the team’s star players. In 1991, he won the Hermann Award as America’s top college player. The Rutgers women also had a strong team in the early 1990s. Their top player was goalkeeper Saskia Webber, who also played for the U.S. women’s team.

Women’s soccer was definitely taking off during this time. Participation at the youth level was growing as players like Mia Hamm led the national team to victory in the 1991 Women’s World Cup. In the years that followed, the national team played several matches in New Jersey, drawing small but enthusiastic audiences. The breakthrough came with the team’s gold medal at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. Women’s soccer was definitely taking off during this time. Participation at the youth level was growing as players like Mia Hamm led the national team to victory in the 1991 Women’s World Cup. In the years that followed, the national team played several matches in New Jersey, drawing small but enthusiastic audiences. The breakthrough came with the team’s gold medal at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta.

Women’s World Cup fever gripped the U.S. in the summer of 1999, when the tournament was held in venues around the US, including Giants Stadium. The opening matches were played in the Meadowlands in front of a jaw-dropping crowd that numbered nearly 80,000. Team USA blanked Demark 3–0, Brazil beat Mexico 7–1.

Prior to the start of World Cup 94, plans were announced for a new men’s pro league, Major League Soccer. The key franchise would be located in Giants Stadium and play as the NY/NJ MetroStars. MLS played its first season in 1996, with Ramos and Meola becoming hometown heroes. In 1998, the team became the MetroStars, dropping their geographical ID. In 2006, the club was purchased by Red Bull and became the New York red Bulls, though they continued to play their games in New Jersey. They reached the MLS Cup final for the first time in 2008. In 2010 the Red Bulls moved into a new stadium in Harrison.

First-Team All-Americans

Ward Chamberlain (Princeton) 1942

Chandler Brewer (Princeton) 1942

Bud Palmer (Princeton) 1942

Butch van Breda Kolff (Princeton) 1946

Robert Rogers (Princeton) 1947

Bill Sheppell (Seton Hall) 1950

James Hanna (Seton Hall) 1950-51

John Santos (Farleigh Dickinson) 1959

Herb Schmidt (Rutgers) 1960

Lee Cook (Trenton State/TCNJ) 1964-65 Saskia Webber

Myron Bakun (NJ Institute of Technology) 1966

Don Fowler (Trenton State/TCNJ) 1969

Carlos Merchan (Farleigh Dickinson) 1975

Paul Milone (Princeton) 1977

Chico Borja (NJ Institute of Technology) 1980

Nena Odim (Princeton [W]) 1980

Dave Masur (Rutgers) 1983

Aidan McCluskey (Farleigh Dickinson) 1983-84

Michael King (Farleigh Dickinson) 1984

Peter Vermes (Rutgers) 1987

Steve Rammel (Rutgers) 1990

Saskia Webber (Rutgers [W]) 1990 & 1992

Alexei Lalas (Rutgers) 1991

Joey Thieman (Princeton) 1992

Pedro Lopes (Rutgers) 1993

Hecor Zamora (Seton Hall) 1993 Alexei Lalas

Jesse Marsh (Princeton) 1995

Sacha Kjestan (Seton Hall) 2004

|